April 25, 2023

By Dan Wall

One of antitrust’s most revered principles is that the antitrust laws “were enacted for ‘the protection of competition, not competitors.” The principle has been invoked on countless occasions when some competitor’s antitrust claim, filed ostensibly to promote consumer interests, actually served only its selfish interests. The antitrust arguments levied against Ticketmaster today by secondary ticketing companies like SeatGeek are a case in point. Resale marketplaces want antitrust law to protect their narrow commercial interests, not anything about competition or consumer welfare. Worse, those commercial interests are about high-volume ticket scalping, which is about as far from consumer welfare as one can get.

You’re sure to hear a lot of complaining from secondary sellers this week after two iconic bands – Pearl Jam and U2 – announced new shows with restricted transfer tickets. Both will use Ticketmaster Face Value Exchange, which allows fans who can’t attend the show for some reason to sell their tickets at the price they paid. In an industry first, both bands also adopted “all-in pricing” so fans see the total cost of a ticket right upfront with no surprises at checkout. These are great developments for fans – and many have gone on social media to applaud restricted transfer tickets as a way to keep tickets prices low. But predictably, scalper lobbyists and mouthpieces claim these innovations hurt fans because they interfere with some supposed “freedom” to resell tickets at a profit.

This is not new. Resale sites have a long history of complaining about anything that might lessen the flow of tickets to the resale marketplace—and of lodging those complaints without regard to obvious consumer interests like reducing fraud. They claimed it was anticompetitive when Ticketmaster transitioned from paper tickets to secure digital ticketing. They claimed every subsequent advance in secure digital ticketing, such as Ticketmaster’s SafeTix® encrypted mobile tickets technology, was anticompetitive. They have attacked artists like Eric Church and Bruce Springsteen for restricting transferability.

The rallying cry for the resale sites is “Fan Freedom” – which not coincidentally is the name of the front group that StubHub and its then-parent eBay formed in 2011 to put a grass roots face on efforts to fight anything that limited ticket transferability. They make a superficially alluring argument that resale is fan-to-fan exchange among consumers who purchased a ticket at face value, as a result own it, and should therefore have the freedom to resell it without interference.

The problem is that every part of that logic chain is misleading or wrong.

In the first place, the business interests at stake have very little to do with the everyday fan who needs to resell tickets because she can’t make the show or because he bought four intending to make a few bucks by selling two. No one in the industry – Ticketmaster and the venues and artists it serves included – would care about ticket resale if that’s what it typically is. In fact, Ticketmaster facilitates face value transfers with its secure digital transfer technologies. What is really going on here, and what explains why resale sites are trying to make ticket transferability an antitrust issue, is that the vast majority of their business is not fan-to-fan resale but rather high-volume professional ticket resellers. They may call themselves fan-to-fan exchanges, but what actually drives these platforms is a multi-billion dollar industry of ticket scalping. And the mother’s milk of that industry is access to tickets, particularly tickets to the most popular shows and sporting events. To the scalpers and the secondary sites that cater to them, anything that restricts transferability is an existential threat, regardless of whether it’s good for the consumer.

It’s well known how we got here. Tickets to live entertainment events are one of the few products that are regularly priced below their market value. There are a number of reasons for that practice, but high on the list is that artists who are trying to cultivate a loyal fan base care about affordability. They understand that not everyone can pay what the market will bear, and they want to ensure that some sizable portion of the venue is affordable to younger or less affluent fans. They just might want to have better odds of selling out, since that makes for a better experience for the band and its fans. And yet artists are confronted with the reality that whenever demand at whatever pricing they choose exceeds supply, they have created a scalping or arbitrage opportunity. The more successful they are, the bigger problem this becomes.

And then in 2000, the year StubHub was formed, internet technologies transformed resale by providing the digital infrastructure for ticket scalping and arbitrage to occur on an industrial scale and with a veneer of legitimacy. At the time, the music industry was focused on a different internet technology, Napster, the peer-to-peer file sharing software that facilitated industrial scale copyright infringement. No one seemed to notice the Napster-like product that StubHub had created, which allowed concert tickets rather than songs to be resold over the internet without any compensation to the artist. StubHub even skirted the anti-scalping laws that most States had but which, not anticipating the internet, were limited to scalping at the event site. StubHub flourished, becoming one of America’s fastest-growing private companies before it was acquired by eBay in January 2007 for a reported $310 million. Thirteen years later Viagogo would acquire it for $4.05 billion. Ticket resale became a $5 billion industry in the U.S. alone.

It should not take more than a moment’s reflection to realize that everyday fans reselling tickets for convenience rather than profit are never going to fuel the likes of StubHub, SeatGeek and Vivid Seats. And they don’t. Vivid Seats does not even pretend to be a fan-to-fan exchange; it serves professional resellers only. And for SeatGeek and StubHub as well, professional resellers that are somehow getting thousands of tickets – far more than anyone could acquire legitimately – fuel the business. The best estimates are that over 70% of their business is serving professional resellers. On every transaction, these resale sites are getting a 25-40% commission from the consumer (and another 10-15% commission from the seller if it is an ordinary fan and not a broker). That is far more than the single digit percentage fee that Ticketmaster and other primary ticketing companies make from their portion of the service charge on the first sale. It is also a business model that works best when (a) as many tickets as possible get to the resale market and (b) resale prices are as high as the market will bear. It does not work at all if artists are able to deliver tickets directly to the fans who want to attend the show at the prices the artist selected because, to state the obvious, those people won’t resell their tickets. They’ll use them instead for their actual intended purpose.

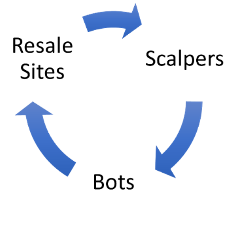

That’s where bots enter the picture – the locust-like automated purchasing technologies that allow scalpers to “cut in line” ahead of real fans and scoop up large quantities of tickets. Despite enormous efforts by Ticketmaster to identify and not sell tickets to bots, far too many succeed. Ticketmaster estimates that 20-30% of the tickets it puts on sale for popular artists are improperly diverted to the secondary market by bots. In extreme cases, brokers using bots acquire as many as 90% of the tickets available for a particular event. Those improperly acquired tickets then go on sale on secondary ticket marketplaces that make no genuine effort to determine the provenance of the tickets. The “see no evil” stance that the likes of StubHub embrace is understandable commercially and legally. Commissions off bot-acquired tickets are money in the bank. And since it is unlawful under the BOTS Act of 2016 to sell tickets when the seller “should have known” they were acquired with bots, it is better not to ask how the seller got them.

The result of this is an unholy alliance between resale sites, brokers willing to use bots, and the purveyors of bot technologies. Below-market pricing by artists attracts scalpers, some of which use bots to acquire tickets, and resale sites happily provide the scale and legitimacy to sell the tickets. This has nothing to do with the fan-to-fan exchange that drives the “fan freedom” narrative. It’s about scalper freedom.

The idea that the fan owns the ticket – it is his or her property – is also false. Concert tickets are revocable licenses issued by the primary ticketing company on behalf of the venue hosting the event. Like software licenses or airline tickets, a concert ticket grants permission, not some unqualified property right. It doesn’t matter that we commonly say that we “bought” the ticket. The license a consumer receives when he “buys” Microsoft Word is to use it, not to resell it. The airline ticket you “bought” allows you to fly but cannot be sold to anyone else. You can book and pay for three nights at a hotel, but you can’t turn around and sell two nights to someone else. Similarly, concert tickets grant permission for the buyers to attend the show.

In American law, the distinction between a “sale” and a “license” is day and night. If a patent or copyright owner sells its patented product, its intellectual property rights are immediately “exhausted” and it has no rights to complain that the product was resold to someone else. But if it licenses the use of the product, the way Microsoft licenses Word, its intellectual property rights remain intact and it can restrict transfer completely or however it chooses. Similarly, since hotels license permission to stay in their rooms, they can prohibit ordinary consumers from reselling those rooms while allowing Expedia to license a block of rooms and “resell” them. The point is that licenses differ fundamentally from sales because they can be and typically are conditional. So, if an artist or team wants to restrict or condition resale for tickets to their shows, they can do that; the venues will happily accommodate that, just as they let the artists and team pick price points and availabilities.

This is why lobbyists for the resale sites are trapsing around the country trying to convince state legislatures to pass laws creating property rights in ticketholders. The idea they have been selling for years that those “property rights” already exist is simply false.

The resale sites are also pushing the fiction that robust resale markets and unrestricted transferability promote consumer welfare. The argument is based on the economic concept of “allocative efficiency,” which in layman’s terms means that an economy functions best when goods and services are distributed to those who value them most and pay accordingly. Resale, the argument goes, increases allocative efficiency because scalpers distribute tickets to those who will pay the most money for them.

This is an argument of convenience, not substance. The economics of scalping have been studied extensively and there is widespread agreement that whatever gains there might be to allocative efficiency, they are more than outweighed by the wealth transfers that flow from consumers to scalpers and from socially wasteful “rent seeking” behaviors such as the use of bots. In any case, it doesn’t take a Ph.D. in economics to figure out that consumers aren’t better off when a $300 ticket sells for $3,000 and the artist doesn’t get a penny of the scalper’s $2,700 profit. That is a world in which scalpers and resale sites are incentivized to get tickets by any means possible, and both artists and consumers are cheated.

The antitrust noise coming from resale sites and their Astroturf advocacy groups is about one thing and one thing only: protecting the flow of enough tickets to the secondary market to support Viagogo’s $4 billion purchase price for StubHub, Vivid Seat’s $1.5 billion market cap, and SeatGeek’s aspirations to go public with a similar valuation. As James Carville might say, “It’s the tickets, stupid!” All the rest, including the antitrust-flavored attacks on Live Nation and Ticketmaster, are just camouflage for the one thing that the resale sites want: government intervention to keep tickets fully transferable. Look at the recently unveiled “Ticket Buyer Bill of Rights” that a coalition of reseller front groups published: two of the “pillars” of this proposal are “The Right to Transferability” and a “Right to Set the Price, so that companies who originally sold the tickets cannot dictate to fans for what price they can or cannot resell their purchased tickets.” Fans would not benefit from this at all. Fans would lose because artists would be stripped of their current ability to restrict sales to real fans at prices the artists choose. The incentives to use bots to steal tickets from real fans would increase.

If the government wants to take action that genuinely helps consumers – which is to say, fans – it should pass federal legislation, preempting contrary State legislation, giving artists, sports teams and other event organizers clear rights to set the resale rules for their shows. The FAIR Ticket Reforms that Live Nation and a broad coalition of artists and artist managers are supporting would accomplish this by codifying artists’ ability to use face-value exchanges and limited transfer to keep pricing lower for fans. That way the market outcome won’t be decided by the endless struggle between the scalpers’ bots and Ticketmaster’s defenses, but by the people who put on the show or the game. Perhaps the outcome will be as in sports, where Ticketmaster, StubHub and SeatGeek have all cut deals with leagues and teams for managed ticket resale. Most likely, there will be artists who don’t care and won’t put any restrictions on resale. But there is no good reason why an artist should not have the same right as a software company or an airline to say this ticket at this price is for you and your friends to see the show, not to build a business by selling it to others.

In the meantime, let’s stop crediting the notion that technologies that permit – but do not mandate – restrictions on ticket transferability violate the antitrust laws. These tools empower hundreds of artists to make individual choices about the best strategy for selling their tickets to their fans. No “monopolist” makes that decision – as StubHub learned when a court threw out its antitrust case trying to claim that the Golden State Warriors monopolized the resale of tickets to Golden State Warriors home games. Ticketmaster does not make that decision either; it just follows the artist’s instructions. So the antitrust attack on Ticketmaster is in reality a disguised attack on artists for exercising the prerogative that every business has to set the prices and terms on which they will do business. It’s a feint, a ruse, a subterfuge – whatever you want to call it. And it is about protecting the selfish interests of one class of competitors, the resellers, not about protecting competition.