This post has now been updated with additional analysis…

By Dan Wall, Executive Vice President, Corporate and Regulatory Affairs, Live Nation Entertainment, Inc

-

This lawsuit against Live Nation and Ticketmaster won’t reduce ticket prices or service fees.

-

There is more competition than ever in the live events market – which is why Ticketmaster’s market share has declined since 2010.

-

Net profits show Live Nation and Ticketmaster do not wield monopoly power.

-

This lawsuit distracts from real solutions that would decrease prices and protect fans – like letting artists cap resale prices.

The Department of Justice and a group of State Attorneys General have now filed the much-anticipated antitrust suit against Live Nation and Ticketmaster. This follows intense political pressure on DOJ to file a lawsuit, and a long-term lobbying campaign from rivals trying to limit competition and ticket brokers seeking government protection for their business model of scooping up concert tickets and jacking up the price.

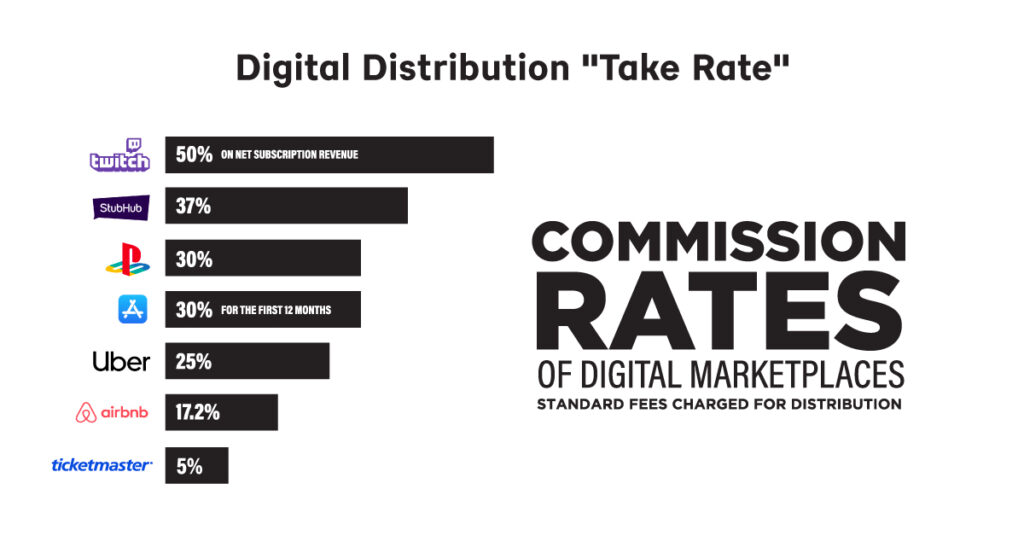

The complaint—and even more so the press conference announcing it—attempt to portray Live Nation and Ticketmaster as the cause of fan frustration with the live entertainment industry. Despite admitting that “[t]he face values of tickets are typically set or approved by artists,” it blames concert promoters and ticketing companies—neither of which control ticket prices—for high ticket prices. It ignores everything that is actually responsible for higher ticket prices, from rising production costs, to artist popularity, to 24/7 online ticket scalping that reveals the public’s willingness to pay far more than primary ticket prices. It blames Live Nation and Ticketmaster for high service charges—and just the fact that there are fees—but ignores that Ticketmaster retains only a modest portion of those fees. In fact, primary ticketing is one of the least expensive digital distributions in the economy.

In light of these data, Assistant Attorney General Kanter’s dodge of a reporter’s question about how much Ticketmaster contributes to fees was telling.

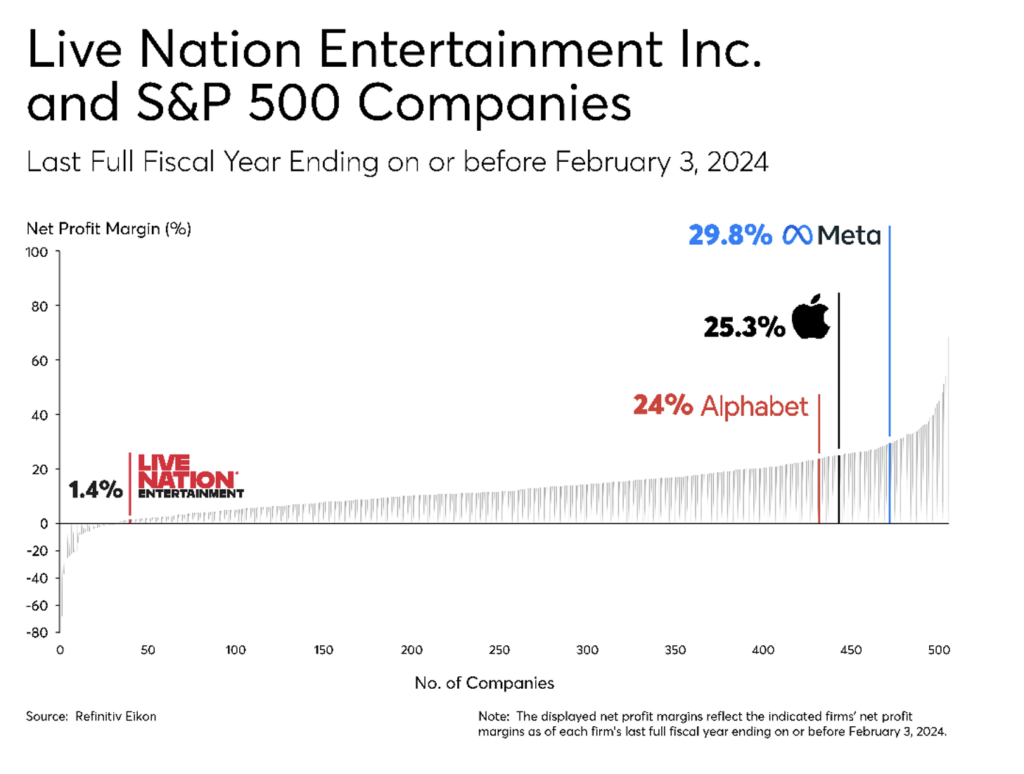

It is also absurd to claim that Live Nation and Ticketmaster wield monopoly power. The defining feature of a monopolist is monopoly profits derived from monopoly pricing. Live Nation in no way fits the profile. Service charges on Ticketmaster are no higher than on SeatGeek, AXS, or other primary ticketing sites, and are frequently lower. In fact, when Ticketmaster loses a venue to SeatGeek, service charges usually go up substantially. And even accounting for sponsorship, an advertising business that helps keep ticket prices down, Live Nation’s overall net profit margin is at the low end of profitable S&P 500 companies.

The trendlines confirm Live Nation’s lack of market power. Every year, competition in the industry drives Live Nation to earn lower take rates from both concert promotion and ticketing. The company is profitable and growing because it helps grow the industry, not because it has market power that squeezes more profit from less output.

In the weeks leading up to today, we met several times with the DOJ front office. It was evident in our discussions that they just did not want to believe the numbers. The data conflicted too much with their preordained narrative that Live Nation belongs in the ranks of the other “tech monopolists” they have targeted.

At bottom, we are another casualty of this Administration’s decision to turn over antitrust enforcement to a populist urge that simply rejects how antitrust law works. Some call this “Anti-Monopoly”, but in reality it is just anti-business. A central tenet of this worldview is that antitrust should target companies that have grown large enough that in some nebulous way they “dominate” markets—even if they attained their size through success in the marketplace, not practices that harm consumers, which is the actual focus of antitrust laws. One of the most jaw-dropping parts of today’s complaint is the assertion that there are “barriers to entry” because “artists naturally prefer to work with a promoter who is successful in promoting many high-demand shows at popular venues”—namely, Live Nation. That is a supreme expression of competition on the merits, winning by being better. But to this group it’s anticompetitive.

The new thinking is also waging war on vertical integration, generally and particularly in the case of so-called “dominant platform companies.” There is no legal basis for objecting to vertical integration on such grounds. Antitrust law views vertical integration as procompetitive in most circumstances. As the leading antitrust treatise states, “vertical integration is ubiquitous and … [in] the great majority of cases no anticompetitive consequences can be attached to it.” And, critically, Live Nation can offer and has offered fans, artists, venues and the rest of the live entertainment ecosystem better prices and better services than they would receive if these complementary businesses were separated. Ticketmaster in particular is a far better, more artist- and fan-focused business under Live Nation’s ownership than it ever was as a standalone company. The complaint is entirely devoid of any response to that inescapable fact—because DOJ has no answer for it.

The Obama Administration saw things differently. It allowed Live Nation and Ticketmaster to merge, and in defending that position acknowledged that there was no legal basis for challenging the vertical aspects of the merger—specifically, allowing a large concert promoter to combine with a large ticketing company. In one filing, it said that it had “determined that it could not prove that the vertical integration resulting from the merger would significantly harm competition in the concert promotion market.” There is no factual basis for concluding otherwise today.

Assistant Attorney General Kanter’s defense of seeking a breakup at today’s press conference provided no reasoning to support a breakup. First, he has his antitrust law wrong, because the DOJ has far more power to challenge a merger, which is unlawful if it is likely to be anticompetitive, than under the monopoly standard which requires evidence of actual anticompetitive effects. So the DOJ cannot shrug off the fact that it allowed Live Nation and Ticketmaster to merge because, as it admitted, it could not prove even a likelihood of anticompetitive effects. And even in this complaint, DOJ does not contend the merger was unlawful. It is just pandering to the crowd with a request for relief that, in my opinion, it cannot possibly hope to achieve under these circumstances.

It is also important that the “other conduct” in this complaint is either exactly what the Obama DOJ addressed in the 2010 Consent Decree or has nothing to do with vertical integration. It is, instead, a grab bag of disconnected alleged practices that could never justify the type structural relief DOJ seeks.

Oak View Group

The complaint makes two principal claims concerning Live Nation’s relationship with the Oak View Group (“OVG”), a venue management company. The first qualifies as disingenuous, in that it is premised on the idea that OVG was a serious potential rival to Live Nation in concert promotion. OVG owns and manages venues. It has never been a concert promoter, nor aspired to be one—which is precisely the point being made in the email DOJ quotes. DOJ’s claim is based on two incidents in which Live Nation and OVG were discussing what to do when an OVG venue wanted to book an occasional show itself on a dark night. To portray that as an agreement not to compete in concert promotion is farcical—particularly when the complaint defines the relevant promotions market as a market for regional or national tours, and explicitly disavows the suggestion that “self-supply” of shows from venue owners is part of that market.

Regardless, OVG’s behavior as a venue operator is fully consistent with every major arena and stadium in the country—they need to have an in house booker who helps fill otherwise dark nights, but they have no interest in systematically taking on the risk of guarantees that could be in the millions of dollars for a show or tens of millions of dollars for a tour.

DOJ also claims it was anticompetitive for Ticketmaster to compete for and win a ticketing contract OVG offered. The theory is that the contract gave Ticketmaster an unfair advantage in securing the business of independent venues that were managed by OVG because it creates financial incentives for OVG to “advocate for” Ticketmaster. But there is nothing remotely anticompetitive about that. Commercial arrangements that involve incentive or marketing payments are common throughout this industry (and many others). Venue management companies like OVG and ASM are in a position to advocate for a variety of service providers, including but by no means limited to ticketing companies. So there is competition for the business opportunities at both the venues they own, which they control, and the venues they manage, which they don’t control but can potentially influence. Ticketmaster competed and won the contract on the merits because OVG determined it was the best ticketing system available.

Threatening Silver Lake

This claim reveals not only a disregard for the facts, but also deep hypocrisy. The current DOJ and FTC have been vocal critics of private equity companies making multiple investments in the same industry because of competitive “entanglements.” So was Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino when, after it had already made an investment in OVG, Silver Lake Partners decided to invest in the Australian live entertainment company, TEG. Rapino’s complaint was fundamentally the same as the DOJ/FTC concern with private equity rollups: it created a conflict between OVG, which had become a close partner to Live Nation, and TEG. So, in December 2021 when a TEG employee wrote to say that it did not intend to compete with Live Nation in the U.S., Rapino replied to Silver Lake’s management that he did not care about TEG, but still had a problem with Silver Lake’s decision to make multiple conflicting investments in the industry.

There is no truth that this brief exchange had anything to do with Silver Lake’s decision to sell its stake in TEG.

Exclusive Contracting

The suit challenges exclusive ticketing contracts between venues and ticketing companies. That is a practice that has been prevalent in the primary ticketing business for decades. In fact, DOJ investigated it in the Clinton Administration and chose not to challenge it because their investigation revealed that venues—the consumers of primary ticketing services—preferred it.

That is still how venues see it, and for good reason. Primary ticketing systems encompass much more than what a fan experiences when buying a ticket online. They are complex venue box office management systems, and each is unique. Very few concert venues want to have more than one because they see it as not worth the added costs and complexity. So, the decision for nearly all concert venues is not whether to have two or more ticketing services providers, but rather which one provider to choose. And because that is how a venue looks at the world, it is no surprise that they—the venues—want to adopt the contracting structure and create the bidding dynamics that will get them the best possible deal from their most desired provider. Competitive bidding for exclusive rights is the proven way for venues to create bidding pressure and maximize the value of their ticketing rights. In other words, exclusivity is a product of competition for venues, not an anticompetitive practice.

Serial Promoter Acquisitions

Another part of the Complaint asserts that Live Nation has violated the law by acquiring, in serial fashion, a number of other concert promoters. The theory is evidently that competition has been thwarted because, but for these acquisitions, the promoters would have acted as significant competitors to Live Nation’s own concert promotion business.

That premise is factually incorrect. During the time period at issue (roughly the last ten years or so), Live Nation has never acquired any U.S. promoter that could plausibly be viewed as a meaningful potential competitor in the alleged national touring market. Look at the example Attorney General Garland raised: Live Nation’s 2016 acquisition of AC Entertainment in Knoxville, Tennessee. This was an acquisition of one promoter, who was in his 60s and looking to retire. He approached Live Nation looking to find a good, long-term home for his employees. Live Nation did not have a Knoxville office, so for $15 million it made the deal. Seriously? The DOJ is challenging that?

In fact, most of our M&A activity in the U.S. has been targeted at discrete areas in which we effectively had no meaningful presence at all—most notably promoting festivals, rather than standard shows or tours—or seizing opportunities to expand into new geographies. A number of these deals, like AC Entertainment, have been with promoters who were on the cusp of retiring and were looking for an alternative to winding down the business. The notion that these acquisitions somehow materially altered the competitive landscape in any way that would be problematic is wholly untenable.

Amps

The Complaint has a variety of allegations around Live Nation’s conduct with respect to amphitheaters it operates. Most surprisingly, the DOJ has alleged that it is anticompetitive tying for Live Nation to exclusively book its own amps. That is legally specious. First, if that is tying, then it is pervasive across the industry. Countless promoters exclusively book venues they own or operate. But it is not tying, legally; DOJ’s tying verbiage is an effort to circumvent the bedrock antitrust principle that no business, even a monopolist, has a duty to deal with competitors. The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed this principle, and the narrow exceptions to it do not apply to this case. Live Nation—and every other vertically-integrated promoter/venue owner—has a nearly unqualified right not to deal with rivals.

The baseless nature of this claim is amplified by the fact that we have—contrary to what DOJ alleges—allowed artists promoted by others to play our amps, and that, as we told DOJ repeatedly, we plan on voluntarily “opening” our amps to artists promoted by others. The claim, therefore, is not only legally groundless but practically pointless.

Content Leveraging and Barclays

For all of DOJ’s rhetoric about seeking “structural remedies” (i.e., a break up of the company), the vast bulk of the conduct the Complaint describes has nothing to do with the combination of a concert promoter and a ticketing company living under one roof. There is one exception, however, which is the set of allegations about threatening or retaliatory conduct by Live Nation, the concert promoter, if venues switch away from Ticketmaster.

This is among the core behavior regulated by the consent decree that DOJ agreed to in connection with the merger of Live Nation and Ticketmaster almost 15 years ago. I have written in detail about the context and background of that agreement elsewhere, and won’t reprise that history here. For present purposes, the key thing to appreciate is that for the past four years, a Monitor appointed by DOJ itself has been keeping close tabs on Ticketmaster’s negotiations with venues and ensuring that the company is not using concert “content” to drive ticketing deals. During that period, covering thousands of such deals, exactly one instance of potential concern has come to the Monitor’s attention. Otherwise, the Monitor has praised Live Nation for its compliance program and an exemplary record of compliance.

The one instance of a potential violation is about the Barclays Center in Brooklyn (referenced but not named in the complaint). What the Complaint alleges about that drama is generally untrue. The short version of a long story is that Barclay’s switched from Ticketmaster to SeatGeek. Six months before that happened, Barclays hired a major New York law firm to threaten us with contract claims and consent decree violations for reducing Live Nation show counts should Barclays switch to SeatGeek. We were scrupulously careful about documenting the business reasons why literally every show in the NY area over the relevant period went to the venue it wound up at. This contemporaneous record unequivocally disproves the contention that there was even a single instance of retaliatory re-routing or anything like it. And as has been reported elsewhere, SeatGeek’s technology and service were not up to the task of servicing major onsales, resulting in Barclays firing SeatGeek, essentially for cause.

More significantly, though, even if DOJ’s version of the Barclay’s story were true (which it is not), violating the consent decree with respect to one venue out of thousands would not amount to a violation of the antitrust laws, which famously concern themselves with “competition, not competitors.” There is a reason this is the only example actually identified in the complaint: despite 18 months of investigation, DOJ found nothing else. At the end of the day, nothing about this isolated incident (which DOJ willfully mischaracterizes) or anything else in this complaint affords any basis for DOJ to disregard, undo and upend the deal it made approving the Live Nation-Ticketmaster merger and its own statements to a federal judge that complaints about that vertical combination lacked merit.

Concluding Thoughts

Live Nation is in the business of bringing the joy of live entertainment to people and to that end connecting artists to fans and supporting a productive live entertainment ecosystem. That is what we do—better than anyone else—and what we will continue to do as we challenge this lawsuit. Is the ticketing marketplace confusing to consumers? Yes, it certainly is. And we have been very clear in the halls of Congress and at the DOJ that we favor genuine reforms that would actually help fans get tickets at the price the artist has set for them to pay. Fans want to see the bands and sports teams they love, and it infuriates them that tickets sell out on Ticketmaster and are then available by the hundreds on secondary online sites at double and triple the cost. But the Government has chosen to do nothing about this. Instead, it has filed a case which misleads the public into thinking that ticket prices will be lower if something is done about Live Nation and Ticketmaster. DOJ is not helping consumers with their actual problems. This is why the government has never been less popular—because they pretend they are fixing your problems when instead they are pandering to a narrow set of political interests.

For additional facts and downloadable graphics please visit: livenationentertainment.com/facts